|

The 2022 AP US History Free-Response Questions have been released to the public! Click here to view the questions on the College Board's website. 2022 APUSH SAQ Sample ResponsesClick here to view my sample responses to the 2022 APUSH SAQ items. 2022 APUSH DBQ Sample Response(s)Click here to view my sample response(s) to the 2022 APUSH DBQ. This file will be updated to include several sample responses that would earn different point values. 2022 APUSH LEQ Sample ResponsesThis year's LEQ 2 asked students to assess the relative importance of causes for the settlement of the British colonies. Click here to see a set of sample responses I've put together for LEQ 2. Take a look at my analysis of the 2022 APUSH Free-Response Questions on Marco Learning's YouTube channel:

0 Comments

In a pandemic year in which most APUSH classes were running behind content-wise, nobody expected the DBQ to be from the post-WWII era! But then, that's exactly what the AP US History Test Development Committee did this year! The 2021 APUSH DBQ topic addressed the social consequences of the prosperity that followed World War II, with a timeframe between 1940 and 1970. Click here to view the 2021 AP US History DBQ

You may find my APUSH DBQ rubric helpful while taking a look at this sample essay, as each of these points is specifically targeted in the sample essay.

One of the major themes of the AP® US History course is migration and settlement. In order to help students prepare for the APUSH exam, I have created a two page review sheet with notes on immigration and internal migrations from the pre-colonial period to the present. Click here to download my APUSH Immigration Review Notes. (PDF Format) Native Migrations ("1491")Around 15,000 years ago, small human populations from Siberia migrated across the Bering Land Bridge. Over thousands of years, these groups spread across North America and developed into several distinct language and culture groups. Exploration and Colonization (1492-1776)European colonizers settled in different regions in North America, with the Spanish settling in the American Southwest and Florida, the French in the Great Lakes region and Louisiana, the Dutch in present-day New York, and the English on the Eastern Seaboard. Of these colonizers, only the English sent large numbers of settlers. During this period, over 300,000 African slaves were brought to North America via the infamous Middle Passage across the Atlantic. Early National America (1776-1820)European settlers during the early national period came primarily from Northwestern Europe (England, Scotland, Germany, and Scandinavia). These settlers were overwhelmingly Protestant. After American independence, 300,000 more African slaves were brought to the United States before Congress ended the African slave trade in 1808. Antebellum Period (1820-1860)In the 1820s, thousands of Anglo-American settlers, mostly from the South, began settling in Texas, which was part of Mexico. In the 1830s, conflicts between these settlers and the Mexican government resulted in Texas declaring its independence in 1836. The 1830 Indian Removal Act resulted in the (often forced) relocation of around 60,000 Native Americans from the South to the Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Thousands died on what became known as the Trail of Tears.

The Wild West (1840-1890)During the 1840s, the height of Manifest Destiny, thousands of American pioneers ventured to the American West on the Oregon, Mormon, and California Trails. The 1849 Gold Rush made California a popular destination for Americans hoping to strike it rich. The Gold Rush also attracted Chinese immigrants, who settled in San Francisco and prospected for gold. In the 1860s, Chinese made up the bulk of the workforce that constructed the Central Pacific Railroad. NATIVISM: The Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), which banned further immigration from China, was the first law passed in the United States to limit immigration. A 1907 “Gentleman’s Agreement” between the United States and Japan limited Japanese immigration without the United States passing a law. The Progressive Era (1890-1920)In the 1890s, as the United States was in the midst of unprecedented industrialization and urbanization, “New Immigrants” arrived in droves from Southern and Eastern Europe (e.g., Italy, Poland, Greece, and Russia). In addition to Italian and Polish Catholics, this represented the first large wave of Jewish and Orthodox Christian immigrants. NATIVISM: The New Immigrants did not get a particularly warm welcome in the United States because they did not tend to speak English, came from countries with little to no experience with republican institutions, and often lacked education and job skills. Progressive reformers worked to culturally assimilate the New Immigrants into an American “melting pot.” The settlement house movement, led by people like Jane Addams (of the Hull House), sought to give immigrants job and language skills. Public education became more focused on citizenship and acquainting new immigrants with the American way of life. Post-WWI (1920s)The (First) Red Scare, which followed the Bolshevik Revolution, was a panic about immigration rooted in fear that immigrants would start a communist revolution in the United States. The Palmer Raids resulted in the deportation of hundreds of immigrants who held radical political views. The Great Migration of African Americans from the South began during World War I, as black men sought jobs in Northern cities and eventually brought their families with them. Unfortunately, many of those trying to escape racism in the South found it in the North in the form of brutal race riots in Chicago and other cities. NATIVISM MEETS RACISM: The (Second) Ku Klux Klan reached its peak membership in the mid-1920s, inspired by the silent film, Birth of a Nation, which glamorized the activities of the (First) Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction. The Ku Klux Klan was as nativist as it was racist, promoting an idea of America that was white, native, and Protestant (WASP). Congress passed Immigration Quota Acts during the 1920s, which laid the foundation for a system of controlled immigration. Quotas, based on national origins, gave preference to immigrants from Northern and Western Europe. The Sacco and Vanzetti Trial was a polarizing event in the 1920s. When Sacco and Vanzetti were found guilty of a murder and armed robbery, Italian-Americans cried foul, claiming that the guilty verdict was based on the defendants’ national origins and anarchist politics. Contemporary America (1960-Present)In the decades following WWII, there was a sustained internal migration to the warm climates of the sun belt (from the Carolinas to California) because of the availability of air conditioning and cheaper (and often less regulated) labor. In the 1960s, national origins quotas were modified in order to encourage more immigration from the developing world - especially from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East - and eliminating preferences for white immigrants. The 1965 act also gave preference to educated immigrants who possessed specialized job skills (e.g., doctors, chemists), immigrants who already had relatives in the United States, and refugees. The Immigration Act of 1990 lifted restrictions against homosexual immigrants, who had been classified among “sexual deviants” in the 1965 Immigration Act. AP® is a trademark registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse, this product.

Topic 7.11 in the AP US History Course and Exam Description addresses Interwar Foreign Policy. One of the key understandings students must have to answer questions about this topic is to understand that while the American public was concerned about the rise of totalitarian regimes, such as Nazi Germany, most Americans opposed direct involvement in the war until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The America First Committee

I have created a practice stimulus-based multiple choice question set featuring an excerpt from one of Charles Lindbergh's speeches. This should be helpful in preparing AP US History students for questions that they might encounter on the exam regarding Interwar foreign policy prior to Pearl Harbor. This is one of fifteen topics from Period 7 of the APUSH course that is subject to assessment.

Click here to download a printable set of these lecture notes.

Historical Context

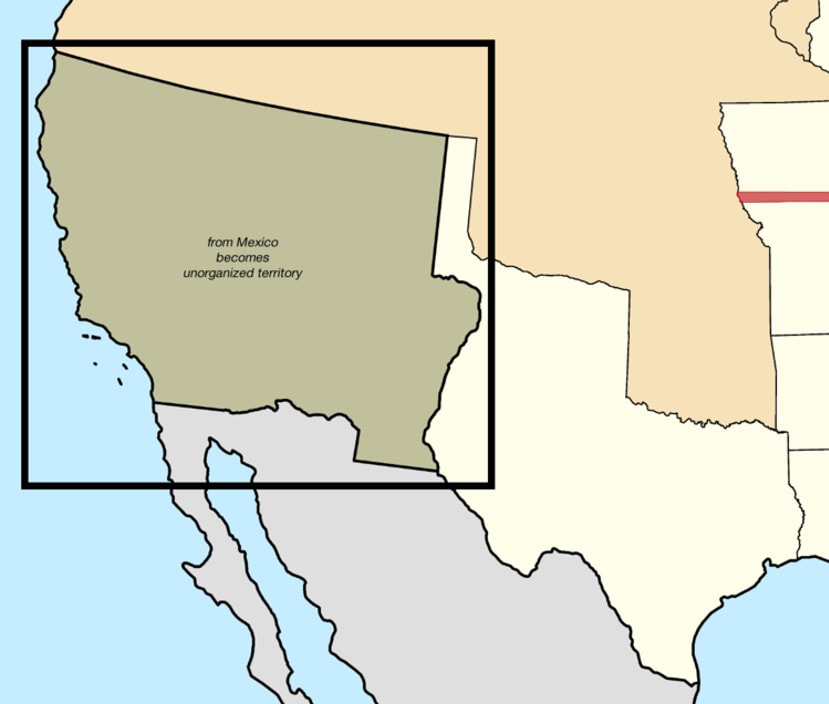

In 1848, the United States annexed the Mexican Cession as part of the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War. The organization of the Mexican Cession became a hot issue in Congress that appeared to be unsolvable, as the doctrine of Free Soil, which prohibited any further expansion of slavery into the American West, gained acceptance in the North while Southern congressmen remained insistent on the existing practice of admitting an equal number of slave and free states into the Union. While it had never passed both houses of Congress, the Wilmot Proviso, with its declaration that slavery would not be allowed in any territories acquired from Mexico, still functioned as a line in the sand for the North.

When California petitioned to enter the Union as a free state, the proposal met resistance from Southern congressmen and it appeared that California would fail to clear the hurdle of the Senate – where the South was nearly equally represented with the North – and fail to attain statehood. Henry Clay, known as the “Great Compromiser,” designed a compromise proposal that he hoped would settle the differences between the sections as he had previously with the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which had ended the Nullification Crisis. This compromise, known as the Compromise of 1850, would be Clay’s last and the final compromise between the sections prior to the American Civil War.

The Compromise of 1850 is divided into five parts:

1. Admit California as a Free State

2. A Stronger Fugitive Slave Act

Although the Constitution required the return of fugitive slaves who had escaped to free states to their owners, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 did not require state governments to cooperate with slave catchers and did not directly involve federal officials in apprehending escaped slaves. This especially concerned representatives of the states of the Upper South, from where it was easiest to escape to free states (Frederick Douglass, for example, had escaped from Maryland). A new and stronger Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed that required state governments to cooperate in the capture of escaped slaves. Additionally, anyone accused of being a slave was to receive a federal bench trial without the benefit of a jury.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was the most controversial part of the Compromise of 1850 and provoked hostility from antislavery activists in the North. Several states, including Wisconsin, Michigan, and Massachusetts, passed “personal liberty laws” that guaranteed jury trials to those accused of being escaped slaves. This resistance, while not formally nullifying the federal law, is considered to be a form of de facto nullification. 3. Popular Sovereignty in New Mexico and Utah Territories

Prior to the Compromise of 1850, Congress had decided the status of slavery in a federal territory when organizing that territory, as it had in the Missouri Compromise thirty years earlier. Given the stalemate between proslavery and Free Soil factions in Congress, this was not going to be possible. In order to break the stalemate, Lewis Cass and Stephen Douglas – both Northern Democrats – proposed popular sovereignty (also known as squatter sovereignty) as a solution. The doctrine of popular sovereignty placed the status of slavery in the hands of the settlers rather than in Congress. The New Mexico and Utah Territories were organized in the Mexican Cession on the basis of popular sovereignty, allowing members of Congress to vote to organize the territories without going on record as supporting or opposing slavery.

4. Texas "Bailout" - Land Ceded for War Debt Assumption

The greatest obstacle to organizing the New Mexico and Utah Territories was that Texas – a slave state – still claimed some of the land that the federal government considered as part of the Mexican Cession. Texas claimed that the Rio Grande formed not only its southern - but also its eastern - border. This included Santa Fe, one of the most important cities in the Mexican Cession. In order to get Texas to relinquish its western land claims, the federal government agreed to pay the state’s outstanding debt of $10 million. As with many conflicts between the federal government and the states, this one was solved by money.

Compromise of 1850 Map (Texas and the Mexican Cession

Map Credit: Golbez (Wikipedia)

5. Slave Trade Abolished in Washington, D.C.

Antislavery members of Congress wanted to see slavery abolished in the nation’s capital, seeing it not only as an affront to their own eyes, but an embarrassment in the eyes of the world, which sent its ambassadors to there. Southern congressmen were equally determined to preserve slavery in the capital, not only as a matter of principle, but as a practical matter since their personal valets traveled to Washington with them. A compromise was reached that prohibited the slave trade in Washington, D.C., but did not abolish the institution of slavery, itself.

Memorizing the Compromise of 1850

It can be difficult to remember five pieces of information by themselves, which is why I encourage students to divide their recollection of the Compromise of 1850 into three smaller parts. The admission of California as a free state (for the North) and the stronger Fugitive Slave Act (for the South) can be seen as an even trade. The organization of the Mexican Cession according to principles of popular sovereignty and the settlement of the Texas boundary in return for debt assumption are both territorial provisions for organizing the Mexican Cession. Finally, the abolition of the slave trade (but not slavery, itself) in Washington, D.C., stands on its own as a compromise between the sections.

The Failure of the Omnibus

Henry Clay initially attempted to pass the Compromise of 1850 as an omnibus bill, in which the entire compromise would be passed by a single vote in each house of Congress. When Clay’s omnibus bill failed, Stephen Douglas built a separate majority to pass each provision of the compromise as a separate bill. Douglas’ approach to the bill took additional work, but it got the job done. Although Clay still gets most of the credit for the Compromise of 1850 as an elder statesman, the younger Douglas – whose presidential aspirations were still ahead of him and not behind him, as Clay’s were – did most of the legwork.

Webster vs. Calhoun: Last Debate of the Great Triumvirate

The Compromise of 1850 represented not only the end of an era of compromise in Congress, but also the end of an era of the political dominance of the generation that came of age during the War of 1812. Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun – known to history as the “Great Triumvirate” – were at the end of their long political careers, having all made their names in the Senate after unsuccessfully pursuing the presidency. While Clay’s role in the compromise has already been addressed, the speeches of Webster and Calhoun illustrate the turning point that the Compromise of 1850 represented in American politics.  Webster Webster

Daniel Webster, a senator from Massachusetts, delivered his “Seventh of March” speech in favor of the compromise. In his opening words, he proclaimed, “I wish to speak to-day, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American,” attempting to interpose himself between the conflicting sections. However, his assertion that, “the South, in my judgment, is right, and the North is wrong,” in reference to the failure of the Northern states to cooperate in the return of escaped fugitive slaves did not sit well with Webster’s constituents, which included noted abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and John Greenleaf Whittier. Whittier wrote a poem, Ichabod, which cast Webster as an angel fallen from glory. In order to escape the ire of his constituents, Webster resigned from the Senate and finished his political career as Millard Fillmore’s Secretary of State.

Calhoun Calhoun

John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who had begun his career as a “War Hawk” and ardent nationalist during James Madison’s presidency, had become the elder statesman of Southern sectionalism and one of the most vocal advocates for the expansion of slavery into the American West. In a speech that was read aloud by a colleague while he watched silently due to advanced illness, Calhoun expressed his opposition to the compromise, believing that the South had already agreed to several compromises and was on its way to compromising itself out of existence. He predicted that the compromise measures, if passed, would lead the nation on an inevitable course toward disunion – a prediction with an air of prophecy.

Why it Matters

The importance of the Compromise of 1850 lies in its status as a turning point in the political culture of the United States. In crafting the Compromise of 1850, Henry Clay used the same strategy that had worked to solve the Missouri question and the Nullification Crisis, both of which had been solved by compromise measures. However, the fruits of Manifest Destiny - the annexation of Texas and the Mexican Cession – ignited new conflicts over the status of slavery that had been settled before these new territories were added to the United States. In addition, the United States was transitioning from an aristocratic political culture based on political compromise to a democratic political culture based on majority rule (for more on this, see my analysis of aristocratic and democratic republics as applied to antebellum politics). Just a few years later, Congress would pass the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed elements of the Missouri Compromise and make slavery possible in areas that had been closed to the peculiar institution in 1820.

The era of Antebellum political compromise ended with the Compromise of 1850. Congress would never admit another slave state, ending the earlier practice of pursuing a parity between slave and free states. No successful political compromise would be reached between the sections until the Compromise of 1877, which ended Reconstruction.

The following key concepts from the AP US History Course Description and Concept Outline are relevant to the Compromise of 1850:

Congressional attempts at political compromise, such as the Missouri Compromise, only temporarily stemmed growing tensions between opponents and defenders of slavery. (Key Concept 4.3) The courts and national leaders made a variety of attempts to resolve the issue of slavery in the territories, including the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and the Dred Scott decision, but these ultimately failed to reduce conflict. (Key Concept 5.2)

ContextAlexander Hamilton had ambitious plans for building a strong central government with an equally strong credit rating. In order to build public credit, Hamilton pushed a plan for the federal government to assume the war debts that the states had incurred during the Revolution. After resisting the measure initially, Jefferson and Madison agreed to the measure in return for an agreement that the federal capital would be moved to a site on the Potomac River on the border of Virginia and Maryland. Hamilton's Whiskey Tax After the federal government took on over $20 million in new debt, Hamilton’s next step was figuring out how to pay for it. As is often the case in history, the people who were chosen to pay for this new debt assumption were not the people who benefitted most from it or even supported it in the first place. To fund this new debt, Hamilton recommended a federal excise tax on whiskey. An excise tax is a tax on the sale of a product or on a product produced for sale (in this case, the latter). Hamilton’s whiskey tax is also an example of a sin tax, which is placed on goods that are deemed luxurious – or even harmful (today, taxes on cigarettes are an example).

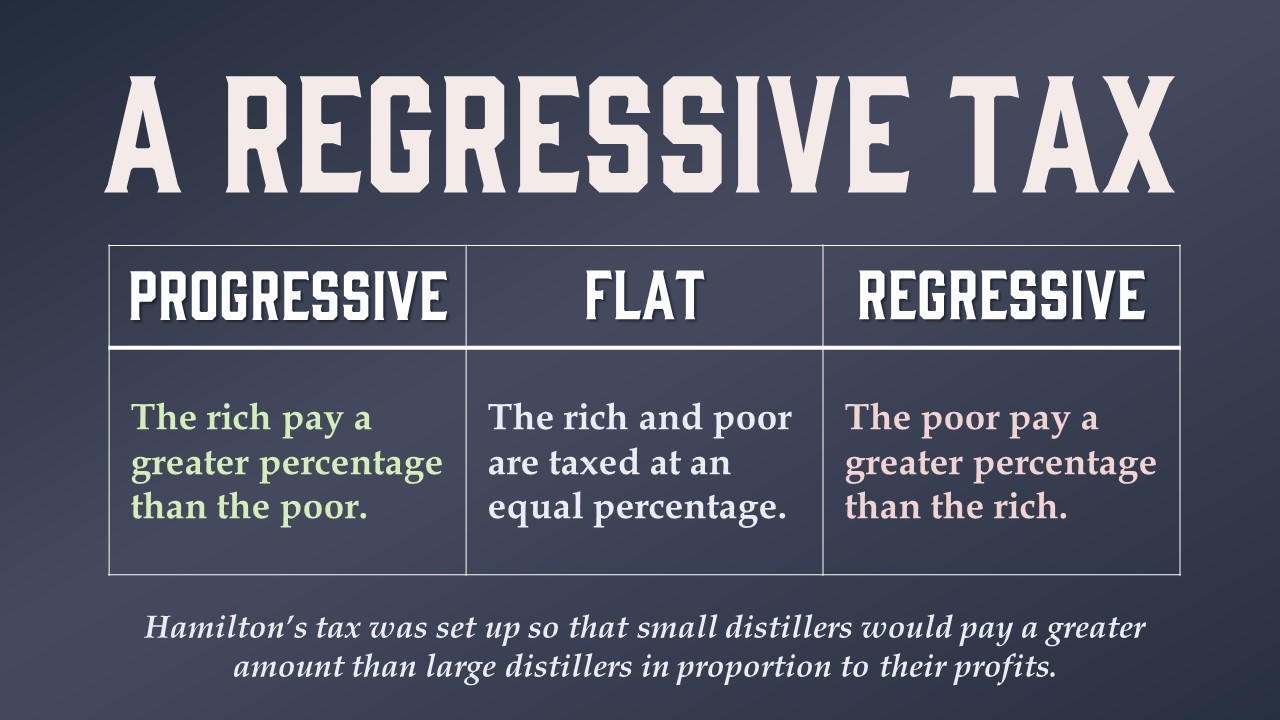

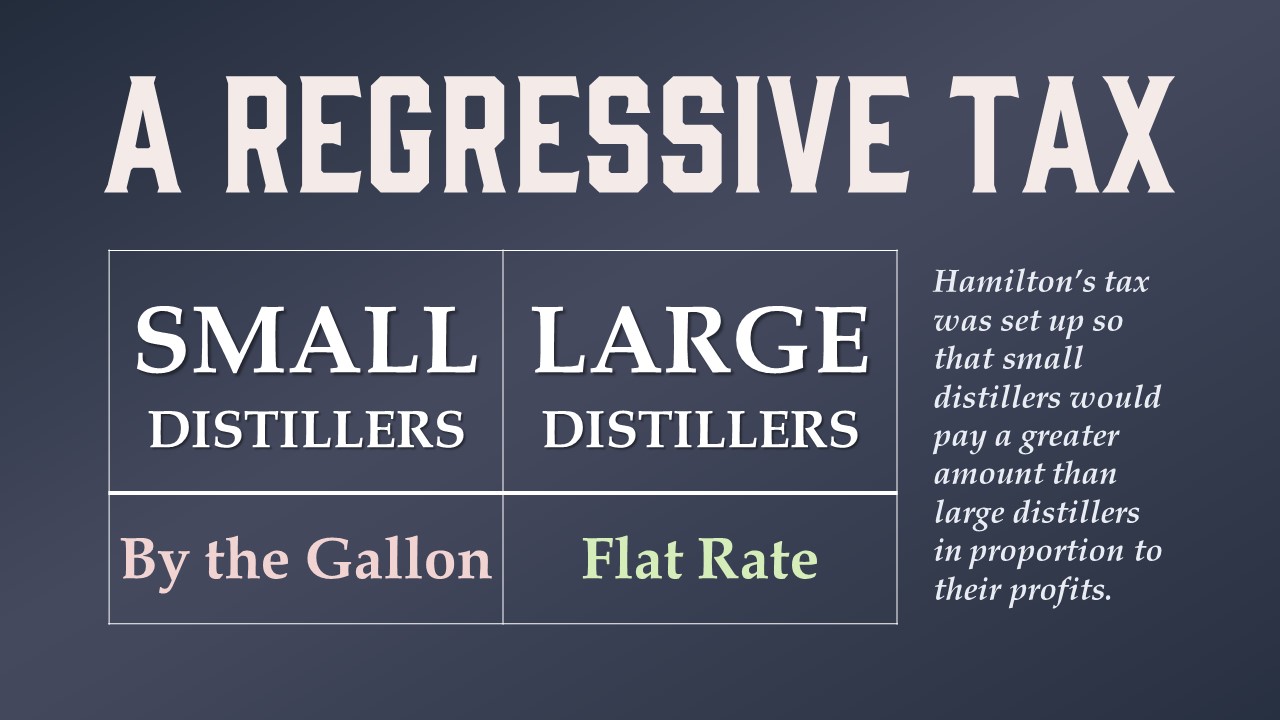

It’s important to note here that Jefferson wanted to explore ways for wine to become cheaper rather than to raise the price of whiskey through taxation. A Regressive TaxHamilton’s whiskey tax hit especially hard in Appalachia, the region of westernmost settlement at the time, where farmers would distill small batches of whiskey for easier transport across the Appalachian Mountains or down the Ohio River to New Orleans. At the time, it was difficult to transport surplus wheat across such long distances, but a farmer could get a good return on a few barrels of whiskey, making for a profitable side hustle for these farmers. Whiskey also served as currency in these Western regions where precious metals and paper money were scarce. Because of these economic realities, Western settlers felt targeted by Hamilton’s tax, which hit them harder than it did Americans living on the Eastern Seaboard. To add insult to injury, Hamilton’s tax was a regressive tax that allowed large distillers to pay a flat rate, while small distillers had to pay by the barrel. At this time, President George Washington was the largest commercial distiller in America. Distillers like Washington could pay a single flat fee and produce as much as they wanted with no additional tax, but Western farmers who lacked the resources to operate on that kind of scale had to pay a tax on every single barrel they produced.

The Whiskey RebellionPopular discontent spread throughout Appalachia and rose to the point of a full-scale rebellion in Western Pennsylvania – specifically, the area around Pittsburgh. The Whiskey Rebellion, as it is known to history, was the third in a line of major frontier settler rebellions. Bacon’s Rebellion in Colonial Virginia and Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts during the Confederation Period followed similar patterns of armed uprising by frontier farmers against Eastern elites. While the American Revolution had some features of these rebellions, it was a cooperative effort between frontier settlers and the colonial elites who supported it. The Whiskey Rebellion was the last of these armed uprisings in the early history of the United States. The organizers of the Whiskey Rebellion used a lot of the same rallying cries and methods that had been used a few decades before during the years leading up to the American Revolution. “No Taxation Without Representation,” shouted the disgruntled crowds. Although Western Pennsylvania was represented in Congress, those who protested against the excise tax saw it as similar to the Stamp Act, where an outside government had taxed the colonies without the consent of their colonial legislatures. No one disputed the authority of the new federal government to collect taxes on imports, but the idea of this new government reaching directly into the pockets of citizens struck many people as a repressive throwback to the days of unfair taxation by Parliament. Just as the Sons of Liberty had used tarring and feathering to intimidate tax collectors, the Whiskey rebels tarred and feathered a federal tax collector, forcing him to “ride the rail” through the town in an old humiliation ritual. Escalation According to Ron Burgundy, a widely respected historian and Scotch connoisseur, the Whiskey Rebellion escalated quickly. According to Ron Burgundy, a widely respected historian and Scotch connoisseur, the Whiskey Rebellion escalated quickly. Between 1792 and 1794, things escalated as the unrest in Western Pennsylvania went from a raucous protest to a full-scale rebellion. Threats were made, effigies were burned, tax collectors were assaulted, and finally, shots were fired by organized groups of armed militiamen. In 1794, Washington decided that the rebellion was too large to be contained by local authorities and worthy of federal attention and gained authorization from Congress to call up a federalized militia. The federal government raised an army of 13,000 men to put down a rebel militia whose size was estimated to be around 500. Once the federal militia was assembled, Washington showed up to personally inspect the troops. Although one historian refers to this as “the first and only time a sitting American president led troops in the field,” this isn’t strictly accurate, as following his inspection, Washington left the army under the command of “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, a Revolutionary War officer who was then serving as governor of Virginia. It was Lee who would lead the army into Western Pennsylvania to put down the rebellion. Ironically, Lee was the father of General Robert E. Lee, the most famous person ever to lead a “rebel army” in the history of the United States. The force assembled by the federal government was so overwhelming that it prompted the small rebel militia to disperse before the federal militia even got there. This was viewed as a massive victory for Hamilton and the Federalists, who had sought to demonstrate the power of the new federal government to put down insurrections – an area where the Confederation government had proven to be woefully inadequate while Shays’ Rebellion had raged on for months in Western Massachusetts. In a gesture of clemency, President Washington pardoned two men who were found guilty of treason and sentenced to hang. Jefferson and the Whiskey Rebellion Although Federalists hailed this as an achievement of a strong central government against anarchist elements intent on undermining its authority, Jefferson viewed the federal government’s response as an overreaction to a minor uprising. “An insurrection was announced and proclaimed and armed against, but could never be found,” Jefferson wrote to James Monroe. Jefferson and Madison believed that Hamilton used the rebellion to advance his own partisan political agenda, casting the Federalist Party as the party of law and order and the Republican Party as the party of rebellion and lawlessness. No matter what Hamilton’s motives were, the unceremonious end of the Whiskey Rebellion put an end to a tradition of armed uprisings of disgruntled whites on the western frontier that had spanned over a century. Resistance against federal policies by disaffected whites would be confined to the political sphere until the 1850s, when violence erupted in Kansas in the years leading up to the Civil War. Sin Tax Error?The long-term victory would rest with the Jeffersonians, as no Federalist would ever hold the presidency again after John Adams lost his bid for re-election in 1800. In the years since, Americans have continued to have debates about how government policies affect the less fortunate, both in terms of the use of government police powers and of fair and equitable taxation – a debate that has shown itself most recently in the presidential candidacies of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. Appalachian voters, angry with elites in Washington, were a key part of the coalition that elected Donald J. Trump as the 45th President of the United States. Politically, Hamilton’s victory proved to be short-lived, as small farmers in Appalachia put aside their bullets and went to the ballot box in protest. Western areas supported Jefferson’s Republican Party overwhelmingly in the elections that followed, leading to a Republican takeover of the White House and both houses of Congress in 1800. As president, Jefferson signed a repeal of Hamilton’s whiskey tax, along with all internal excise taxes, preferring to fund the government through revenue tariffs. “It may be the pleasure and pride of an American to ask,” Jefferson stated in his Second Inaugural Address, “what farmer, what mechanic, what laborer, ever sees a tax-gatherer of the United States?” Further Reading:

Dumas Malone, Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty (University of Virginia Press, 1962) The first two party system in the United States began around 1791 during George Washington's presidency and lasted until the 1816 presidential election following the War of 1812. Jefferson vs. HamiltonGeorge Washington's cabinet (which included only four men) was dominated by Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, and Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State. The differences between Jefferson and Hamilton regarding the powers of the central government, the proper interpretation of the Constitution, the economy, and foreign policy quickly degenerated into partisanship as other political leaders rallied around Jefferson and Hamilton. Hamilton favored a strong, active, and energetic central government, while Jefferson advocated for a limited federal government that would respect the rights of the states. John Adams sided with the Federalists in spite of some personal and political disagreements with Hamilton, while Jefferson was joined by his close friend, James Madison. Madison's alignment with Jefferson is significant because it represented an end to the political alliance between Madison and Hamilton that produced The Federalist Papers. It's important to note here that the first two party system wasn't a simple continuation of the debate over the ratification of the Constitution between the Federalists and the Antifederalists, although there certainly were some correlations. While nearly everyone who had opposed the ratification of the Constitution would have been gravitated toward Jefferson's party, there were those who, like Madison (the "Father of the Constitution), had advocated strongly for ratification, yet saw Hamilton's plans to strengthen the central government as exceeding the powers delegated by the Constitution. Federalists vs. [Jeffersonian] Republicans

It's important to distinguish Jefferson's Republican Party from the Republican Party that exists in the United States today. The present-day Republican Party was founded in the 1850s after the breakup of the Second Party System. In order to avoid confusion, historians have traditionally referred to Jefferson's party as the Jeffersonian Republican Party, although the "Democratic-Republican" terminology used by political scientists has lately become more common (in spite of its historical inaccuracy). Strong Central Government vs. States' RightsThe difference between the Federalists and the Republicans concerned the role of the central government. Although the Constitution was drafted and ratified in order to create a stronger central government than had existed under the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution still retained many features of federalism, which limited the power of the central government. In The Federalist Papers, Madison specifically reassured states' rights advocates that the Constitution would not destroy the power of state governments. "The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite." -- Federalist No. 45 (Madison)

The Fears of the Federalists

While Federalists feared anarchy, Jefferson and Madison were much more fearful of tyranny. During Shays' Rebellion, Jefferson wrote to Madison, "a little rebellion now and then is a good thing." Rationally, Jefferson did not see how one rebellion in a single state threatened the existence of the United States, but he feared that a strong central government could place the states at risk of having their rights stripped away as they had been at the outset of the American Revolution. "I am not a friend to a very energetic government," Jefferson wrote, "It is always oppressive." This view of government was behind all of Jefferson's efforts to keep the power of the central government as limited as possible, fearing oppression (which he had experienced) more than anarchy (which he had not experienced). Strict vs. Loose Construction of the ConstitutionIn order to limit the power of the central government, Jefferson interpreted the Constitution as a strict constructionist. To Jefferson, the government only had the powers that were enumerated (specifically listed or numbered) in the Constitution. Hamilton, a loose constructionist, advocated for the doctrine of implied powers, claiming that by granting some powers to the central government in the Constitution, the Framers had implied a grant of other powers that will assist the government in executing the enumerated powers.

Constituents: The Support Bases of the Federalists and RepublicansEvery political movement in a society with representative government depends highly upon the constituencies being represented by each political faction. Hamilton and the Federalists drew their support largely from Northeastern coastal areas that were highly dependent on commerce. These were the same people who had advocated most strongly for a stronger central government that would have the power to control trade. The Northeast was also cultivating a manufacturing sector, which Hamilton sought to use the power of the central government to promote.

Economic Development vs. Laissez-FaireAlexander Hamilton believed that the future of the United States as a powerful nation depended on the development of a manufacturing sector on par with that of Britain. He believed that government would be an essential support for building a manufacturing sector that would make the United States an economic and military power. Jefferson, who saw no need for domestic manufacturing when the United States could trade for European manufactured goods, resisted Hamilton's plans to develop a manufacturing sector. Jefferson advocated for a laissez-faire (let it be) approach by government toward economic involvement. His ideas were influenced not only by his devotion to agriculture, but also by the influence of Adam Smith's recently published book, Wealth of Nations, which advocated laissez-faire and free trade as the best paths to economic growth. Jefferson's "hands off" approach contrasted with Hamilton's "hands on" approach to government's role in the economy. The National BankBy far, the most famous disagreement between Jefferson and Hamilton was on the issue of the national bank. Hamilton believed that the establishment of a national bank was "necessary and proper" for helping the government to execute its enumerated powers in the financial sector, such as collecting taxes, borrowing money, and coining money. Jefferson saw Hamilton's plan for a national bank as an unconstitutional seizure of power by the federal government. At no point does the Constitution ever explicitly authorize Congress to charter a bank. Jefferson also opposed the bank on economic grounds, as he believed that it would increase the central government's role in the economy and work for the benefit of commercial and manufacturing interests. He advised President George Washington to veto the bill that created the First Bank of the United States, but Washington ultimately went with Hamilton's advice on the matter. To download the primary sources from which I've drawn these quotes, click here. Protective Tariff vs. Free TradeIn order to help with the establishment of a domestic manufacturing industry, Hamilton advocated for a tariff that was higher than what was necessary to fund the government, known as a protective tariff. A protective tariff would artificially increase the price of foreign manufactured goods in order to encourage Americans to buy more expensive products manufactured domestically, which would help with the growth of domestic manufacturing. Jefferson opposed protective tariffs for both constitutional and economic reasons. Southern farmers who depended on foreign trade would find themselves paying more for the manufactured goods that they bought from Europe, so Jefferson's laissez-faire approach benefited them most. In addition, the Constitution empowers the government to levy taxes in order to "pay the Debts and provide for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United States." Since the objective of a protective tariff meets none of these criteria, Jeffersonians believed that such a tariff was unconstitutional and that only revenue tariffs should be imposed by the central government. The constitutionality of protective tariffs would continue to be a divisive issue in the United States for decades, culminating in the Nullification Crisis following the Tariff of 1828. Federal Assumption of State War DebtsOne of Alexander Hamilton's goals was to build public credit. At the time the Constitution was ratified, the United States government had a massive debt that it was making little progress in repaying. Some states, such as Massachusetts, had similar debt problems as a result of the Revolutionary War. In order to effectively build public credit, Hamilton proposed that the federal government assume the war debts of the states. Jefferson opposed Hamilton's plan to assume state debts because it would bind the states more closely together and strengthen the central government. Also, as a Virginian, he came from a state that had paid its war debts in full and would have to pay the war debts of other states under Hamilton's plan. In what is known as the "Dinner Table Compromise" (or the Compromise of 1790), Hamilton got Jefferson and Madison to go along with his plan for the federal government to assume state war debts in return for a promise that the federal capital would be moved from New York (the financial center of the United States) to a site on the Potomac River that separated Virginia from Maryland. Jefferson and Madison believed that this would remove the government from the influence of the financial sector and that this would outweigh the impact of Hamilton's debt assumption plan, but today, the federal government can hardly be considered outside of the influence of New York's powerful financial sector. Foreign Policy: France vs. Britain

Hamilton and the Federalists did not share Jefferson's enthusiasm for the French Revolution, believing it to be a threat to the stability of Europe. Hamilton was an admirer of the British system of government and saw the French Republic as going far beyond that form of balanced government into something that could degenerate into mob rule. Jefferson was disappointed when Washington issued his Neutrality Proclamation in response to the war between France and Britain. In spite of this disappointment, Jefferson would later come to appreciate what would become one of George Washington's most enduring presidential legacies and the centerpiece of his famous Farewell Address. The End of the First Two Party SystemThe first two party system in the United States lasted through the War of 1812, after which Federalist leaders were branded in the popular mind as un-American due to their role in the ill-fated Hartford Convention. James Monroe's election as president ushered in a brief period of non-partisanship known as the "Era of Good Feelings."

Compared to the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution, the American Revolution was a relatively tame affair. This has led many historians to characterize it as little more than a political revolution that left the same elite class in control of American politics (minus the British supervision) and resulted in few - if any - meaningful changes to American society. But then, to characterize the American Revolution as a mere political turnover overlooks some important ways in which the Revolution was an important turning point in American society.

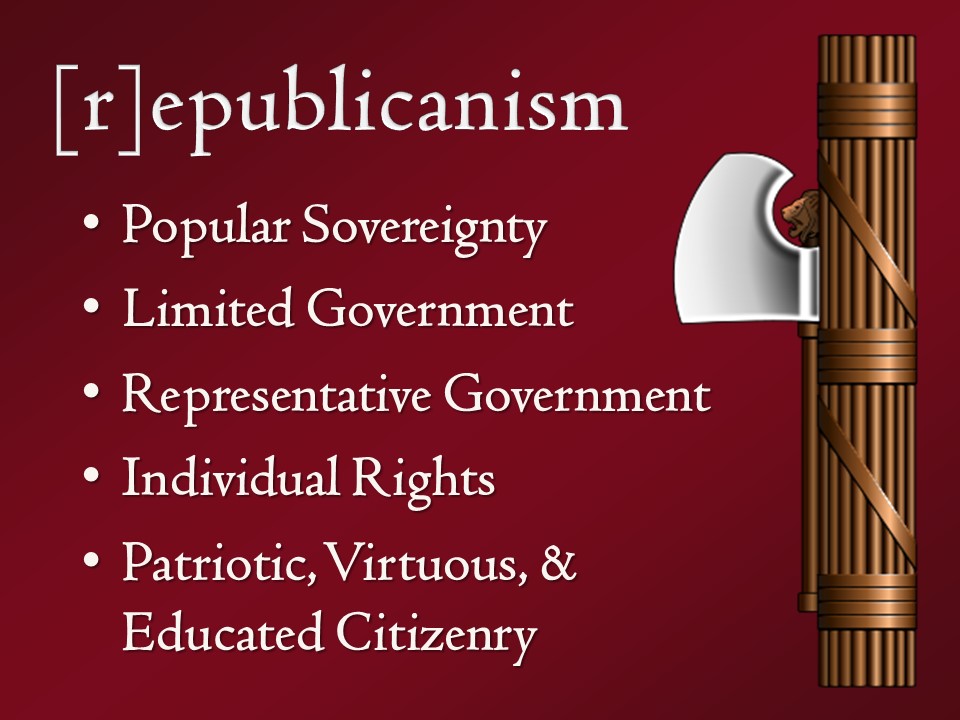

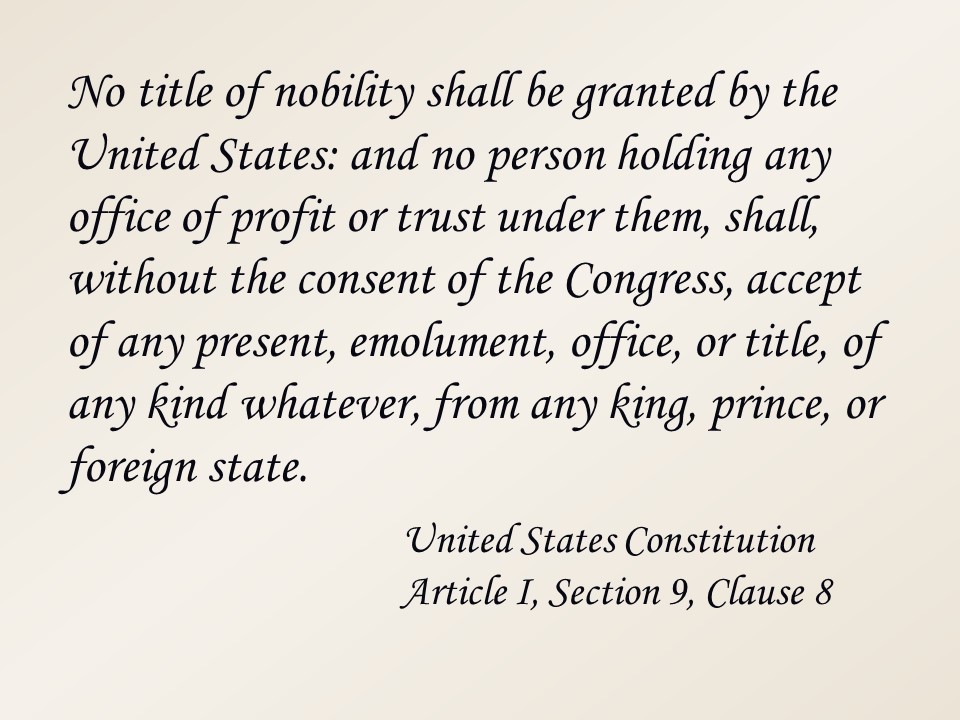

Since a republic is administered by citizens, it is important that these citizens have a sense of patriotism and are educated in their civic responsibilities. Those who lead in a republic are expected to carry themselves with simplicity and perform their duties without regard to personal gain or profit. EgalitarianismWhile some citizens in a republic are wealthier than others, republics are more egalitarian in their social structure than monarchies. Before the Revolution, some states, such as Virginia, had primogeniture laws on the books that allowed for the firstborn son of a family to receive the lion's share of the inheritance (this kept the family's wealth together). Although Richard Hofstadter noted in The American Political Tradition that primogeniture had largely fallen out of use by the time of the American Revolution, Thomas Jefferson still considered the abolition of Virginia's primogeniture law a victory for republicanism, as it formally abolished a practice common in monarchical societies.

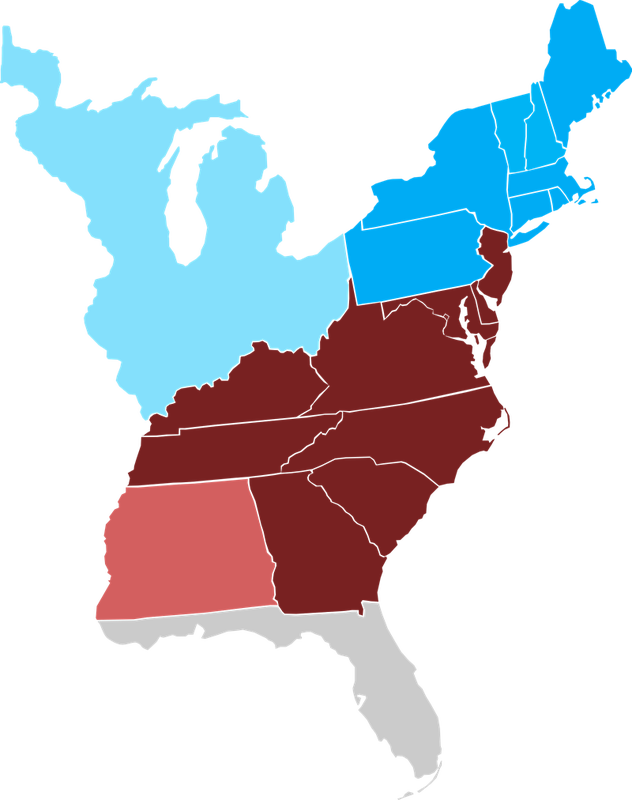

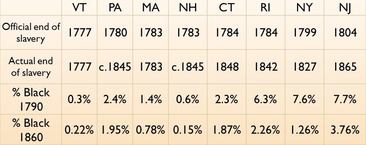

Emancipation in the North

In the South, where slavery was central to the cash crop economy, no progress was made toward emancipation, although the founding generation had faith that slavery would be phased out at some point. Unfortunately, that did not come to pass and slavery became even more entrenched in the South in the 19th century. Religious Freedom

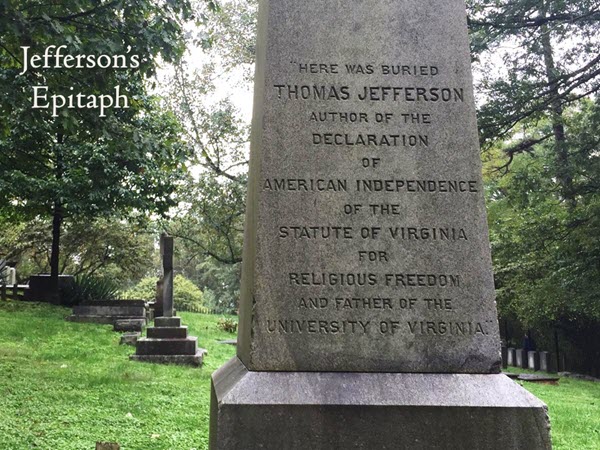

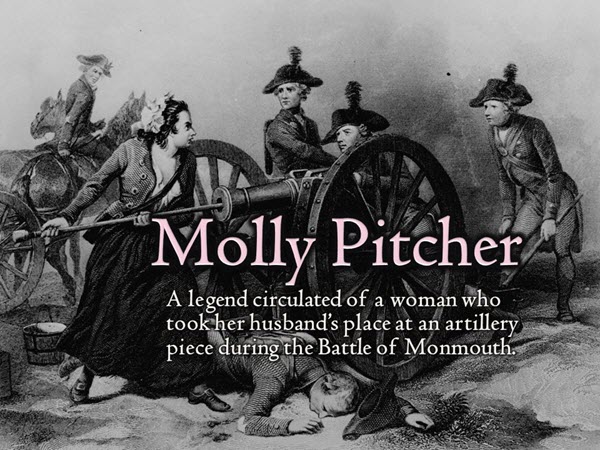

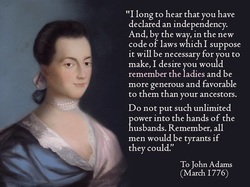

Jefferson was so proud of his authorship of the Virginia Declaration for Religious Freedom that he specifically listed it as one of the three accomplishments he wanted on his epitaph - the other two accomplishments being his role in authoring the Declaration of Independence and in founding the University of Virginia. There is no mention of Jefferson's presidency on his gravestone, an indication that Jefferson was much more concerned about what he did to spread freedom and enlightenment than with what offices he had occupied. This is very much in line with the republican view of public service as a civic duty rather than as a stepping stone to self-aggrandizement and wealth. Women and the American Revolution

Another famous heroine of the Revolution was Nancy Morgan Hart, a Georgia patriot was said to have taken a small group of Tory loyalists captive and even shot one of them when he ignored her warning not to move. Today, Hart County is the only county in Georgia that is named after a woman.

While Adams' hopes of political equality for women would not be realized until the passage of the 19th Amendment after World War I, republicanism called for women to play an active role in the civic education of their sons. In order to fulfill the duties of republican motherhood, women had to receive an education, as well. Agrarianism

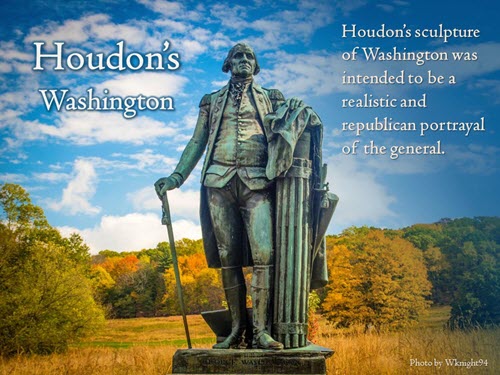

George Washington: [r]epublican Soldier

As a leader, Washington consciously set out to follow the example of Cincinnatus, a hero of the Roman Republic. Cincinnatus was given the dictatorship, which he could have retained for up to six months, and gave it back to the people after only sixteen days. After the Revolutionary War, Washington voluntarily resigned his commission with the intention of fully retiring from public life. Even as president, he stepped down voluntarily after two terms, surrendering power as soon as he had gotten the new nation on its feet. Upon his death, Washington made one final nod to the principles of republicanism by emancipating his slaves.

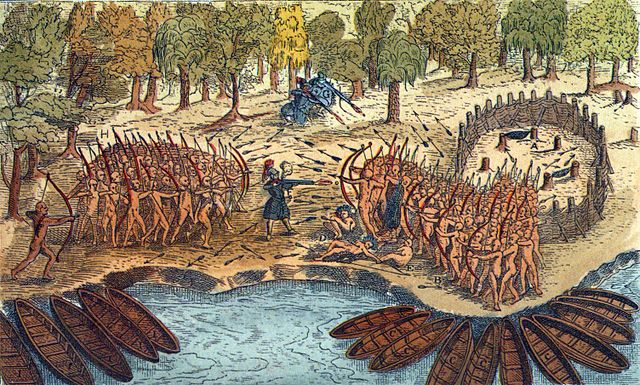

In the new AP US History curriculum, Key Concept 1.1 focuses on the development of Native American societies in the years preceding and immediately following European contact.

Key ConceptsThere are three broad ideas that a student really needs to understand in order to be successful when questioned about this topic on the AP US History exam:

Nomadic vs Settled TribesWhile some tribes - especially in the North - subsisted exclusively on hunting and gathering, most Indian tribes employed agriculture for at least part of their food supply. Tribes that subsisted on hunting and gathering tended to be nomadic, while tribes that depended more heavily on agriculture built more permanent settlements. Those living close to rivers, lakes, and oceans also fished.

Geographical Culture Groups

Gender RolesIn societies that practiced hunting, gathering, and agriculture, women tended to do the lion’s share of agricultural labor, while men spent most of their time hunting. Early European colonists believed that Native men were lazy and oppressed their women, but from their cultural standpoint, this was simply a different division of labor (Native men wondered why European men did "women's work" on the farm).

|

Tom RicheyI teach history and government Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed