|

Click here to download a printable set of these lecture notes.

Historical Context

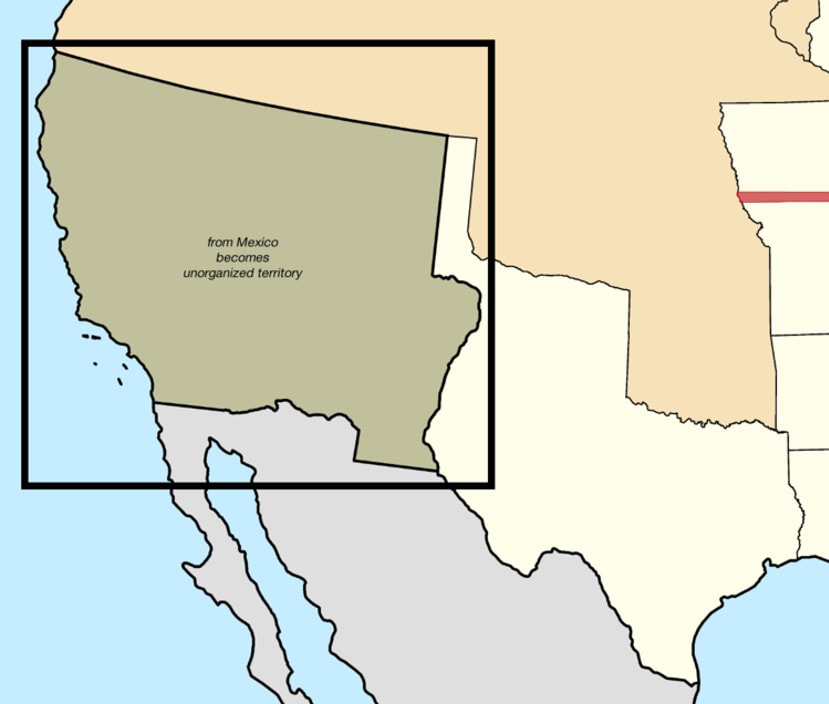

In 1848, the United States annexed the Mexican Cession as part of the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War. The organization of the Mexican Cession became a hot issue in Congress that appeared to be unsolvable, as the doctrine of Free Soil, which prohibited any further expansion of slavery into the American West, gained acceptance in the North while Southern congressmen remained insistent on the existing practice of admitting an equal number of slave and free states into the Union. While it had never passed both houses of Congress, the Wilmot Proviso, with its declaration that slavery would not be allowed in any territories acquired from Mexico, still functioned as a line in the sand for the North.

When California petitioned to enter the Union as a free state, the proposal met resistance from Southern congressmen and it appeared that California would fail to clear the hurdle of the Senate – where the South was nearly equally represented with the North – and fail to attain statehood. Henry Clay, known as the “Great Compromiser,” designed a compromise proposal that he hoped would settle the differences between the sections as he had previously with the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which had ended the Nullification Crisis. This compromise, known as the Compromise of 1850, would be Clay’s last and the final compromise between the sections prior to the American Civil War.

The Compromise of 1850 is divided into five parts:

1. Admit California as a Free State

2. A Stronger Fugitive Slave Act

Although the Constitution required the return of fugitive slaves who had escaped to free states to their owners, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 did not require state governments to cooperate with slave catchers and did not directly involve federal officials in apprehending escaped slaves. This especially concerned representatives of the states of the Upper South, from where it was easiest to escape to free states (Frederick Douglass, for example, had escaped from Maryland). A new and stronger Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed that required state governments to cooperate in the capture of escaped slaves. Additionally, anyone accused of being a slave was to receive a federal bench trial without the benefit of a jury.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was the most controversial part of the Compromise of 1850 and provoked hostility from antislavery activists in the North. Several states, including Wisconsin, Michigan, and Massachusetts, passed “personal liberty laws” that guaranteed jury trials to those accused of being escaped slaves. This resistance, while not formally nullifying the federal law, is considered to be a form of de facto nullification. 3. Popular Sovereignty in New Mexico and Utah Territories

Prior to the Compromise of 1850, Congress had decided the status of slavery in a federal territory when organizing that territory, as it had in the Missouri Compromise thirty years earlier. Given the stalemate between proslavery and Free Soil factions in Congress, this was not going to be possible. In order to break the stalemate, Lewis Cass and Stephen Douglas – both Northern Democrats – proposed popular sovereignty (also known as squatter sovereignty) as a solution. The doctrine of popular sovereignty placed the status of slavery in the hands of the settlers rather than in Congress. The New Mexico and Utah Territories were organized in the Mexican Cession on the basis of popular sovereignty, allowing members of Congress to vote to organize the territories without going on record as supporting or opposing slavery.

4. Texas "Bailout" - Land Ceded for War Debt Assumption

The greatest obstacle to organizing the New Mexico and Utah Territories was that Texas – a slave state – still claimed some of the land that the federal government considered as part of the Mexican Cession. Texas claimed that the Rio Grande formed not only its southern - but also its eastern - border. This included Santa Fe, one of the most important cities in the Mexican Cession. In order to get Texas to relinquish its western land claims, the federal government agreed to pay the state’s outstanding debt of $10 million. As with many conflicts between the federal government and the states, this one was solved by money.

Compromise of 1850 Map (Texas and the Mexican Cession

Map Credit: Golbez (Wikipedia)

5. Slave Trade Abolished in Washington, D.C.

Antislavery members of Congress wanted to see slavery abolished in the nation’s capital, seeing it not only as an affront to their own eyes, but an embarrassment in the eyes of the world, which sent its ambassadors to there. Southern congressmen were equally determined to preserve slavery in the capital, not only as a matter of principle, but as a practical matter since their personal valets traveled to Washington with them. A compromise was reached that prohibited the slave trade in Washington, D.C., but did not abolish the institution of slavery, itself.

Memorizing the Compromise of 1850

It can be difficult to remember five pieces of information by themselves, which is why I encourage students to divide their recollection of the Compromise of 1850 into three smaller parts. The admission of California as a free state (for the North) and the stronger Fugitive Slave Act (for the South) can be seen as an even trade. The organization of the Mexican Cession according to principles of popular sovereignty and the settlement of the Texas boundary in return for debt assumption are both territorial provisions for organizing the Mexican Cession. Finally, the abolition of the slave trade (but not slavery, itself) in Washington, D.C., stands on its own as a compromise between the sections.

The Failure of the Omnibus

Henry Clay initially attempted to pass the Compromise of 1850 as an omnibus bill, in which the entire compromise would be passed by a single vote in each house of Congress. When Clay’s omnibus bill failed, Stephen Douglas built a separate majority to pass each provision of the compromise as a separate bill. Douglas’ approach to the bill took additional work, but it got the job done. Although Clay still gets most of the credit for the Compromise of 1850 as an elder statesman, the younger Douglas – whose presidential aspirations were still ahead of him and not behind him, as Clay’s were – did most of the legwork.

Webster vs. Calhoun: Last Debate of the Great Triumvirate

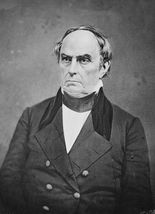

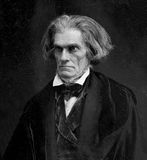

The Compromise of 1850 represented not only the end of an era of compromise in Congress, but also the end of an era of the political dominance of the generation that came of age during the War of 1812. Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun – known to history as the “Great Triumvirate” – were at the end of their long political careers, having all made their names in the Senate after unsuccessfully pursuing the presidency. While Clay’s role in the compromise has already been addressed, the speeches of Webster and Calhoun illustrate the turning point that the Compromise of 1850 represented in American politics.  Webster Webster

Daniel Webster, a senator from Massachusetts, delivered his “Seventh of March” speech in favor of the compromise. In his opening words, he proclaimed, “I wish to speak to-day, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American,” attempting to interpose himself between the conflicting sections. However, his assertion that, “the South, in my judgment, is right, and the North is wrong,” in reference to the failure of the Northern states to cooperate in the return of escaped fugitive slaves did not sit well with Webster’s constituents, which included noted abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and John Greenleaf Whittier. Whittier wrote a poem, Ichabod, which cast Webster as an angel fallen from glory. In order to escape the ire of his constituents, Webster resigned from the Senate and finished his political career as Millard Fillmore’s Secretary of State.

Calhoun Calhoun

John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who had begun his career as a “War Hawk” and ardent nationalist during James Madison’s presidency, had become the elder statesman of Southern sectionalism and one of the most vocal advocates for the expansion of slavery into the American West. In a speech that was read aloud by a colleague while he watched silently due to advanced illness, Calhoun expressed his opposition to the compromise, believing that the South had already agreed to several compromises and was on its way to compromising itself out of existence. He predicted that the compromise measures, if passed, would lead the nation on an inevitable course toward disunion – a prediction with an air of prophecy.

Why it Matters

The importance of the Compromise of 1850 lies in its status as a turning point in the political culture of the United States. In crafting the Compromise of 1850, Henry Clay used the same strategy that had worked to solve the Missouri question and the Nullification Crisis, both of which had been solved by compromise measures. However, the fruits of Manifest Destiny - the annexation of Texas and the Mexican Cession – ignited new conflicts over the status of slavery that had been settled before these new territories were added to the United States. In addition, the United States was transitioning from an aristocratic political culture based on political compromise to a democratic political culture based on majority rule (for more on this, see my analysis of aristocratic and democratic republics as applied to antebellum politics). Just a few years later, Congress would pass the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed elements of the Missouri Compromise and make slavery possible in areas that had been closed to the peculiar institution in 1820.

The era of Antebellum political compromise ended with the Compromise of 1850. Congress would never admit another slave state, ending the earlier practice of pursuing a parity between slave and free states. No successful political compromise would be reached between the sections until the Compromise of 1877, which ended Reconstruction.

The following key concepts from the AP US History Course Description and Concept Outline are relevant to the Compromise of 1850:

Congressional attempts at political compromise, such as the Missouri Compromise, only temporarily stemmed growing tensions between opponents and defenders of slavery. (Key Concept 4.3) The courts and national leaders made a variety of attempts to resolve the issue of slavery in the territories, including the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and the Dred Scott decision, but these ultimately failed to reduce conflict. (Key Concept 5.2)

3 Comments

Joel Gillham

12/29/2018 02:37:04 am

Hi Tom it's Jlord from the life stream.

Reply

bruh moment

8/11/2019 07:32:03 pm

That's an absolute bruh moment

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Tom RicheyI teach history and government Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed